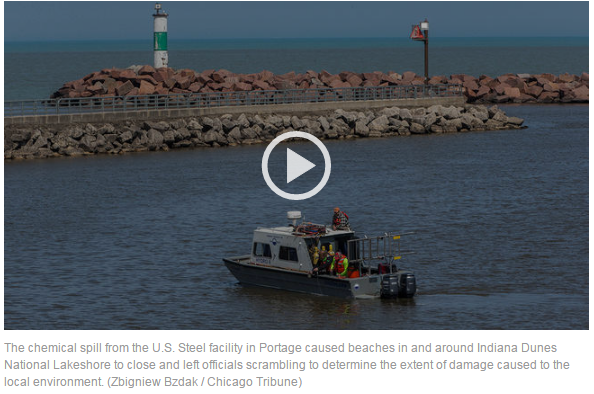

U.S. Steel failed to test a Lake Michigan tributary for highly toxic hexavalent chromium after blue liquid “with visible solids” poured out of one of the company’s northwest Indiana plants in late October, according to documents posted online Tuesday by state regulators.

The incident marked the second time this year that the company’s Midwest Plant spilled chromium into Burns Waterway, a man-made slip that flows into the lake near a sprawling complex of steel mills dividing the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore.

An inspector from the Indiana Department of Environmental Management visited the plant Nov. 16, a day after the Tribune first reported on the latest spill. Plant managers told the inspector they had opted not to test for the most dangerous form of the metal, even though the earlier spill in April had released up to 920 pounds of hexavalent chromium into the water.

In a report on the visit, the state inspector was about as incredulous as a bureaucrat can get, pointing out that “Visual evidence of operational deficiencies, such as discolored effluent or solids leaving the facility … should lead the facility to monitor for hexavalent chromium to determine the extent of the impact, even if the on-site personnel believe there will be none or little.”

Steel mills are required to regularly conduct two types of tests for chromium. One measures total chromium, including a significantly less toxic form known as trivalent chromium. The other targets hexavalent chromium, a metal made infamous by the movie “Erin Brockovich.” It is so dangerous that the Midwest Plant’s water pollution permit limits daily discharges to 0.51 pounds.

The October spill discharged 56.7 pounds of total chromium into the Lake Michigan tributary, an amount 89 percent higher than the plant’s permit allows over 24 hours. More chromium likely would have poured into the water if a contractor hadn’t noticed an overflowing treatment tank and notified plant managers, according to the inspection report.

U.S. Steel said in a statement that it already has retrained its treatment plant operators and tweaked its monitoring equipment. The company’s response echoed a statement it released after the April incident.

“U.S. Steel has made enhancements to the parts of the facility where the failure occurred and is reviewing additional measures it can take to allow for earlier detection of future issues,” the April statement said, adding that company officials are “committed to the safety of our employees, to the communities in which we operate and to protecting the environment.”

U.S. Steel reported the latest spill in a letter that asked Indiana regulators to keep it secret. Law students at the University of Chicago discovered the letter last month while researching pollution problems at factories along the southwest shore of Lake Michigan for Surfrider, a nonprofit group that represents Great Lakes surfers.

“It is shocking and mind-boggling,” Mark Templeton, director of the Abrams Environmental Law Clinic at U. of C., said about the new documents. “Once U.S. Steel observed that the illegal chromium discharge was blue and full of solids, did they not run the test because they didn’t want to know the results?”

Templeton is preparing a lawsuit that will accuse U.S. Steel of repeatedly violating the federal Clean Water Act since 2011. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced last month that the city is drafting its own lawsuit, citing the steel mill’s close proximity to a Lake Michigan drinking water intake off 68th Street.